Librarian Was My Occupation – Remembering the Occupy Wall Street People’s Libary

In the fall of 2011, the angry shout of “we are the 99%!” could be heard echoing in localities big and small across the US. The movement had seemed to come out of nowhere, forcing politicians to figure out how to respond, while the media struggled to think of how to cover the movement, even as the various encampments drew bigger and bigger crowds. For roughly two months, by its very presence the Occupy movement sounded the alarm that our economic, political, and societal systems were failing to meet the needs of most people. And then, by the end of November, the movement was crushed—with politicians pretending they had heard the concerns, while the media went back to acting as though all was well.

Much has changed in the ten years since Occupy Wall Street, much has stayed the same in the ten years since Occupy Wall Street. And the changes that have occurred have not necessarily been for the best.

Ten year anniversaries are generally occasions to look back with the benefit of hindsight and ruminate on what was. Librarianshipwreck (this here website) was started by two friends who met while participating in the People’s Library at Occupy Wall Street. The original idea for this blog was that it would be a space to continue thinking about some of the issues that we were thinking about while participating in the People’s Library, and other OWS offshoots. Clearly, the content of this site has changed over the years, but it owes its origin to a friendship between two librarians that started during Occupy Wall Street. So, on the occasion of the ten year anniversary J and Z had a conversation (conducted over email), looking back at OWS and the People’s Library and thinking about what they still mean today.

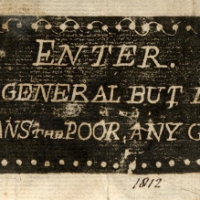

Before you jump into this reflection, you may want to read the history of the People’s Library we wrote at the time: Librarian Is My Occupation: A History of the People’s Library of Occupy Wall Street

Z:

So, ten years after Occupy Wall Street (and the People’s Library), when you think back to those two months in the park (and the next several years of OWS related organizing and activism in New York)—what do you think Occupy was? How do you explain it to people when they ask you about it today?

J:

How to explain it? I think it needs to be seen in context for it to make sense. OWS was as long after the anti-war mobilizations against the post-9/11 wars in Afghanistan and Iraq (which in turn came just after, and to some extent overlapped with, the anti-globalization movement of the mid-late 1990s) as we are now from OWS. And the last ten years have seen what feels like non-stop big lifts on things like Black Lives Matter, police & prison abolition, student debt, Medicare for All, fighting back against nascent neo-fascism, and trying not to all die of climate change or COVID. Whether one was already politically active when OWS came around or if that was one’s first foray into that kind of political work, it feels like we haven’t had a quiet moment since.

But within that context, it really was a turning point. There was so much going wrong for so many people after the W. Bush years, with the wars and the economy, and Obama’s election was supposed to spark changes that never came. And then the dam broke open all at once. People who had never before involved themselves in street politics found themselves learning about direct action and consensus decision making; getting pepper sprayed and beaten by cops; and realizing that they are closer to the subaltern than to the powers that be. So many people experienced the world in a way they never had before and were shocked into ongoing solidarity by the experience. I think that’s what has led us to where we are today, where ideas like abolition or erasing student debt are commonly discussed, even if derisively. OWS and its ripples moved the Overton window quite a few clicks to the left and radicalized a lot of people.

Despite that, we are living in hell, ten years on. Maybe I’ll ask you about that later, since doom is your thing. We both experienced the occupation largely through our work in the People’s Library, while also having day jobs as librarians. Thinking back, what do you recall that being like, moving between the two kinds of library atmospheres?

Z:

That context is such an important thing to remember in all of this. Throughout the Trump years it was really strange to watch Bush transform in the popular memory from being a reviled warmonger into this kindly Texan grandpa who paints pictures of his dog. It seems that a lot of people have forgotten how much genuine hope there was in the air when Obama was elected. And I think you’re right that something that was undergirding a lot of OWS was a sense of disappointment and disenchantment. In the park there was definitely a hardcore of serious leftist/activist types (anarchists, socialists [this was before it became more socially acceptable to call yourself a socialist]), but more than anything I just remember there being so many disappointed Democrats who were hopeful that what was going on in the park(s) would push the Democrats to do more. In some ways I remember OWS feeling like a moment when many people were saying that they had been waiting patiently for the Democrats to act, but they were done waiting. Though I think we can talk more about some of the political legacies of OWS in a little bit.

As for your library question, seeing as we probably should be talking about libraries here, it was definitely always an amusing thing to be working in the People’s Library and to have someone come up to you and gruffly ask “oh yeah, and what do you really do?” and be able to respond to them with “I’m a librarian.” During OWS I hadn’t yet been a “real” librarian for very long, I had only graduated from library school the previous May and since then I’d been trying to cobble an income together by doing a lot of different part-time library jobs. It was a pretty hectic time for me as I was running between part-time positions, trying to apply for full-time jobs, and trying to be at the park as much as possible. Honestly, if I had been working a standard 9 to 5 I probably wouldn’t have been able to be at the park as much—but the experience of precariousness was definitely something that made OWS resonate even more for me. I have a distinct memory of being at the park one day and having some guy yelling “get a job” at us, and I remember yelling back “I have three jobs!” Though I guess it was four jobs if you counted the People’s Library.

Juggling so many part-time jobs while applying for full-time jobs was definitely diminishing the original enthusiasm with which I had pursued librarianship. The funny thing is that OWS is what really reaffirmed my love for libraries. I had definitely been naïve and idealistic when I started library school, and I really believed that libraries could be a model for an entirely different way of organizing society…but then once I started working in libraries that enthusiasm was quickly crushed out of me. But the People’s Library really made me feel like there was something special about being able to talk to someone, hear what they were thinking about, hear what they were looking for, and then go help them find the books that would help them take the next steps. There were days where I’d be doing rather similar things at my part-time library jobs and in the park, but in the park it felt like it really mattered.

Same question back to you—though I know the library atmosphere you were coming from wasn’t the most traditional library atmosphere. And on that same wavelength, what kind of library do you think the People’s Library really was?

J:

Oh, gosh, I worked a 9-5 all throughout the occupation and afterwards, and it really was a lot. As you noted, I wasn’t in a proper library then. I had finished library school, where I’d taken an archives management concentration, in August 2009, while the economy was in freefall. It took me about a year to find a full-time job, and I finally landed in a gallery in New York, thanks to my undergrad alma mater’s old girls’ network. I worked with their photo archives and reference library, maintained databases of artist information and sales prices, researched and copyedited for catalogs; and did a little bit of everything. Among your several part-time jobs, I recall that you freelanced with us for a little while, working on a catalogue raisonne. On one hand, I’m glad I was fully employed throughout, since I didn’t have to worry about my personal place in Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. And my bosses fancied themselves the kind of well-off aging New York liberals who were vaguely supportive, so that when a coworker spilled the beans about seeing me in the park it wasn’t really a problem. On the other hand… Being involved in the occupation had the time and energy commitment of a full-time job. I would work all day, leave my office in Chelsea at 5, hustle down to the park by 5:30 or so, and then be there until at least 10, sometimes as late as midnight. I’d drag myself home to Brooklyn, fall into bed, and then get up at 7 the next morning to get on the subway to work and repeat the cycle. On the weekends I would get to the park around noon and be there until late at night. I’d give myself Monday evenings off and go straight home from work, run to the laundromat before they closed, and then get to sleep as early as I could. If friends wanted to spend time with me, they’d have to come to the park and ride along as I worked in the library. Even date nights frequently looked like meeting someone after work & taking a long walk down to the park, stopping for dinner or a drink along the way. I don’t think I had a full night’s sleep for a year. Looking back, it’s absolutely bonkers, and I can hardly believe we did that.

Exhaustion aside — and I truly think I have not yet recovered from the exhaustion, even a decade on — I think splitting my time between librarianship at the gallery and librarianship at the occupation served me as a petri dish in which I could watch capitalism and its malcontents in sharp contrast. It helped me understand what was going on in my work life by supplying terms and ideas for what I was experiencing, while also putting a sharp point on our collective political development by seeing theory in action every day. While I had been politically active since the anti-war years of the Bush administration, I would not be where I am today, politically speaking, without OWS. And a lot of people had that experience, regardless of where exactly they were starting from, whether it was realizing that liberal politics are not the same as left politics or experiencing police violence for the first time.

Looking at what kind of library the People’s Library was, I stand by the conclusions we made at the time. In 2014, we wrote, “We functioned like a traditional library, only with better air circulation, a less reliable roof, and a distinct lack of walls.” The People’s Library was an awful lot like a regular public library. We had a collection with broad coverage (including A LOT of romance novels) shaped by our patrons; we had movie nights, poetry readings, and author talks, along with spotty utilities and napping homeless patrons; and our mission was to provide information, education and leisure resources to a wide swath of the public in a way that centered the library’s use to its visitors. If only actual public libraries were run by consensus of their workers.

We’ve written in the past about libraries as third spaces, and that was even more true for the People’s Library than it is for regular public libraries. At its best, the occupation of Zuccotti Park as a whole functioned as a third space, a public clearinghouse of sociability, and the library’s space in the northeast corner was a space within that space, where comrades and visitors could find a little bit of refuge from the noise and crowd elsewhere in the park. I’ve been thinking a lot lately, as the university I now work for has begun the fall semester and campus is for better or worse full of students again, about third spaces, and particularly about the loss of public life during the pandemic. When we can’t be physically together for so long, how do we maintain a public life, third spaces, and the commons?

These are some of the ideas that we wrote about several years ago, when the experience was still fresh in our minds. Has your thinking about libraries as place and space changed at all over the intervening years?

Z:

Occupy was definitely exhausting, but it was such an exhilarating exhaustion. At least for the two months that we were actually in the park. I don’t remember sleeping much either, but I felt like any time I walked into the park I had more energy than I knew what to do with. Granted, in the aftermath of the raid, doing any kind of Occupy work was absolutely draining. I know that we were both still heavily involved in Occupy related activities in the weeks, months, and years after the park—but most of those activities always felt overshadowed by the experience of defeat. I remember being tasked by the library working group with sorting through all of the books we eventually were able to recover after the raid, and sifting through all of that stuff was just such a crushing experience: trying to do a preservation assessment of the ruins.

I think that our previous comments on library’s as a third space are still valid. Though, I feel like we have to note that the idea of libraries as a third space is not something that we came up with on our own. And I don’t think that in Occupy it was just the library that was a third space. If the idea of a third space is all about the need for there to be real public spaces that are available to people, I think that Occupy tried to do that in a lot of respects. When I look back at it now, I often find that I think less about the fact that so many of the Occupy encampments had libraries, and more about the fact that so many of the encampments had some kind of medical tent. It continues to be striking to me how many of the things that were parts of the encampments represented the sorts of things that people wanted to see in their societies, but that they didn’t feel they had sufficient access to, for one reason or another. One of the things that was always so enjoyable about the People’s Library is that you got to see and hear how warmly people felt about the idea of libraries—which is a feeling you often miss out on when you’re actually sitting at a reference desk for an eight hour shift.

My attitudes on libraries as spaces has definitely been impacted in the years after Occupy by working full-time in libraries. You and I both worked for quite a few years at a sort of quasi-academic library (where I was working as a reference librarian), and after leaving New York (but before the pandemic) I was working part-time at another academic library. Academic libraries are definitely strange spaces, most of them are technically open to the public, but for the most part you only really see students, independent researchers, and academics there. I know that we had been joking a little bit when we talked about how the People’s Library didn’t have walls—and while the People’s Library didn’t have walls in a literal sense, I think what made it so special was that it didn’t have certain metaphorical walls either. The matter of how we knock down the metaphorical walls that block people from getting into and making the most of libraries is still a big issue. And of course, a lot of this brings up larger questions of power and control. One of the things that was so wonderful about the People’s Library is that the decisions were being made by the people who were part of the group—and anyone could join that group. Individual members of the working group had a lot of autonomy, but we also were mindful of consensus. That’s quite different from working in a library and having to do it a certain way because your boss says so, or because this wealthy donor wants it done in a particular way, regardless of whether or not those are really the right decisions. Watching a library go through major remodeling in which the actual library staff is not consulted…well it really makes you long for working in a library where the librarians (broadly defined) were in charge.

I won’t lie, my experiences working in libraries have had some real ups and downs. There’s a reason why I decided to leave librarianship to go back to school (even though I have been working in libraries while back in school, and even as I imagine I’ll wind up returning to libraries). In some respects working in libraries has been a great experience, and in other respects it has been a really terrible experience. And whenever I talk to people who are thinking about going to library school I always try to encourage them not to romanticize libraries so much.

That being said, I still absolutely love the idea of libraries. Naïve though it may be, I still think that libraries represent this little utopian seed that has been planted beneath the concrete in our society that sometimes gets to send green shoots up through the pavement. I continue to believe that libraries are one of the few spaces that people can point to in their own lives and world that demonstrates that there is a way of organizing things that doesn’t have to be about money—it can be about sharing. I love the ways in which libraries represent a sense of shared abundance, albeit an abundance that can only exist insofar as we are willing to share it. I suppose that I’m saying that I still love the idea of libraries, I still love what libraries can be…but I’m also very aware of the realities of actually existing libraries.

I’d be very curious to hear your thoughts on that especially seeing as you’ve largely been working on the more technological side of libraries for the last several years. I’d also be interested in hearing what you think are the legacies of Occupy and the People’s Library?

J:

My current and previous jobs are both back of the house, whether we call that technical services, metadata & discovery, or library systems. I spend my days up to my elbows in the software that contains, searches & displays library collections and their metadata. It’s a wild world! It’s never boring (except when it is), and there tends to be more job security than in other library specialties, so I’m glad I landed where I am. It’s also the specialty that, along with acquisitions, has to interface with capitalism the most. I wrote about some of that recently. In systems, we are confronting all of the problems and contradictions capitalism continues to bring to bear on libraries, such as privacy, the digital divide, accessibility, and the pervasive market logic of neoliberalism. While I was largely not working in systems during OWS, the straightforwardness of the work in the People’s Library could be a breath of fresh air. We had minimal contact with vendors of either materials or software, and we weren’t particularly concerned about anything like a budget. Certainly, we did have some technical capacity — tap lights, a wifi hotspot, electricity until the FDNY absconded with our generators, and a handful of very basic laptops — but that was never our focus. And that’s for the best, since the question you’ve recommended adding to Postman’s list of what to ask about technologies was very apt for our situation — what happens when you hit it with a rock? What happens in an unseasonable snow? What happens when you have to pack it all up and move it to New Jersey for a night? What happens if you leave it outside in a box for two months? What happens when police throw it in a garbage truck?

My thoughts about the legacy come down to two things. First, as I started with, we have to situate ourselves in a historical arc that reaches at least back to the anti-globalization movement and will continue to reach forward at least into our near future. We have been in a period of backlash and revanchism, both attempted and realized, for some time now. The most obvious example of that is the mere fact of the Trump administration. We can also look towards the rise of hyper-masculine, mostly white formations from Proud Boys to the Bundy ranch; the response of police & their unions to the very idea that they shouldn’t shoot Black people willy-nilly; anti-trans and anti-abortion legislation….I could go on. That backlash is not the fault of the popular leftward push of OWS in 2011 & 2012, but it is in response to it. It is not surprising that it has happened, either, as a passing familiarity with history shows that this is always what happens — those who have traditionally held undeserved power have a temper tantrum and try to grab it back after they see even a suggestion that they might lose a little bit of that power. That’s where we are right now.

The flipside, though, is that that hard leftward push we made is also still here. The right might be trying to claw its way back to hegemony, but so many left ideas have become mainstream (even when not enacted) over the last ten years. Forgiving student loans. Prison and police abolition. Taxing the hell out of rich people and corporations. Housing as a human right instead of a commodity. Universal healthcare. None of this could be discussed with any seriousness in the mainstream before the occupation. We really did completely change the narrative. Heck, democratic socialist candidates regularly win local elections all over the country now.

The second legacy is what I said to Jeff Wilson when he was creating his graphic novel, The Instinct for Cooperation — the occupation functioned as a clearinghouse for radicals and their projects. For the first time in years, and possibly at a larger scale than had ever been done before, people on the left were connected. Especially in a big place like New York City, it was entirely possible that there would be people, projects or organizations that you wanted to work with, but that you’d never even find out about. The occupation brought us all together — and brought in people who weren’t already trying to work on left politics — in the same place and time. We got to know one another, and we worked together on common goals for weeks and months. Occupiers became friends, helped each other get jobs, rented apartments together, started families. Even outside of New York, we made long-lasting connections with comrades in other cities — Jay Kelly in Boston, for example, or Rachel Allshiny in Chicago. This all means that future political projects are able to start from that footing, which is a great advantage. The real revolution, it turns out, is the friends we made along the way.

Z:

Your point about the anti-globalization moment is really key. There are some people who were stunned by Occupy because they had forgotten that there was much of the left, well, left in the US. The years of the war on terror saw a lot of activism around the wars, but the anti-globalization movement that had been really revving up in the late 90s seemed to die down a bit, and as huge as some of those anti-war protests were at the time, I think that many people forget just how nationalistic and jingoistic the US was throughout much of the Bush administration.

The ways in which the politics have shifted seems essential here as well. On the one hand we really are seeing a resurgence of the far-right, in terms of the groups you mentioned, and also in terms of the even more overtly authoritarian shift that we’ve been seeing in the Republican party. And though I know that leftists love to complain online about particular elected “left” officials, you’re right that it’s pretty significant that we can now point to multiple prominent elected officials who don’t run away and grab a gun whenever somebody calls them a socialist. I’m always a bit suspicious of heavily deterministic narratives that argue that without Occupy we wouldn’t be seeing figures like AOC get elected; however, I definitely do think that Occupy deserves some credit for shifting some of the discourse. I always found the “we are the 99%” line kind of hokey, but I do think that Occupy really shoved the issue of income inequality back into the forefront. I don’t think it was so much that “Occupy made it okay to critique capitalism,” but that because Occupy kind of took a firm “this capitalism thing isn’t actually working for most of us” stance, it shifted the whole dialogue to create more of a space where critiques could be voiced…even if they rarely reached the same level of radicalism as the things that were coming out of Occupy.

But, at risk of being a caricature of myself (I do study disasters and doom-saying, after all), I think that there are three other significant things that have happened since Occupy that really need to be considered as contrast where we were 10 years ago with where we are now. The first, and this is the hopeful one, is that I think that in the last few years (since around 2016) we have seen a somewhat more critical attitude towards the tech companies emerge. Around the time of Occupy there was such a massive narrative about how “Facebook made this possible” or how “Twitter made this possible.” I mean, if you go back and look at the initial call for OWS in Adbusters it wasn’t for “Occupy Wall Street” it was for “#occupywallstreet.” It was literally a hashtag, and the hashtag came first. I definitely remember arguing a lot with people in Occupy about companies like Facebook and Twitter, and I’m glad that in recent years it has become increasingly obvious that the tech companies are not our friends.

The second big thing that I think should be mentioned is that the climate catastrophe is getting closer (indeed, it is already happening, it just isn’t evenly distributed). There was certainly a lot of environmental concern in Occupy, but I think that when we consider the present political moment and what makes it different form 2011, the fact that climate exacerbated disasters are piling up seems really significant. I feel like one of the things that was great about Occupy was it seemed to echo that line from Rabbi Hillel “If not now when?” and I think that this same sense is particularly striking in terms of climate action now. And yet, even as there is this intense feeling of justified urgency, it keeps getting smashed against the rock of slothful action on the part of the government. Within the climate movement there is some real division amongst activists about just how bad the situation currently is, but it feels safe to say that pretty much everyone in the climate movement would say that we have a lot of work to do and not a lot of time left in which to do it. And in linking this back to Occupy a bit more, it does seem like within even mainstream climate discourse it is becoming increasingly common to see an acknowledgement of the way that capitalism is driving this crisis.

And third, I really think that we have to acknowledge the significance of the pandemic. A big part of Occupy was saying to people “these institutions don’t actually work for you,” but I think one of the things the pandemic has done is made many more people realize “these institutions do not work.” I continue to believe that most people haven’t really started to process what an absolute catastrophe this pandemic has been; granted, at this point I think most people are tuning it out. Yet I think that the pandemic presents some real challenges for the left to think about: first, the experience of an ongoing disaster has really sapped a lot of people of hope, and people are getting more and more accustomed to living in the midst of things collapsing; second, Occupy had this grand unifying call to it, but one of the things the pandemic has made devastatingly clear is that it’s really difficult to speak of a “we” that sees itself as a genuine “we” in this country. But, as I said…I always have doom and gloom on my mind.

So, let’s finish this off, what would you say gives you hope in this moment? What do you think comes next?

J:

It’s funny/not funny that, of the two of us, you are generally considered to be the gloomy one, but I tend to think that you’ve got a lot more hope than I do. I don’t really have much hope right now; if I had to make a bet, I’d bet on humanity losing. The pandemic drags on, ultimately because of the selfishness of white people. I think it’s probably too late to prevent the worst ravages of climate change; if it isn’t, it will be soon and I doubt we’ll change course before then. Neoliberal capitalism and resulting wealth disparity are only accelerating, in large part due to the tech companies you’ve just mentioned.

The only place I have a lot of hope right now is around labor. While the labor movement has been gaining slow momentum in the last decade or so — yes, I think that’s another thing OWS breathed some life into — the pandemic has cracked it open. For once, it’s disaster labor power, not just disaster capitalism. Labor has more power right now than it has in half a century, and capital is shitting its pants and furiously writing op-eds about it. That’s what gives me hope right now. If labor will grab as much of that power as we can, we will be able to not only improve our own lives through improving our wages and working conditions, but also be able to use the structures and power of organized labor to work on all that other stuff. My union, for example, does “bargaining for the common good” and has bargaining proposals on the table that address climate change and racial equity. So, fingers crossed that’s what comes next; I’m hoping that we come out of this with a lasting cultural shift around work and a balance of power that favors labor over capital.

Z:

Damnit! I can’t believe that you’re leaving it to me to provide some kind of vaguely hopeful final word! So, in that spirit I’ll just offer my favorite quote as a closing:

“I do not believe that things will turn out well, but the idea that they might is of decisive importance.” – Max Horkheimer

And I’ll note that I first discovered that quote when I was reshelving books in the People’s Library ten years ago.

Related Content

Librarian Is My Occupation: A History of the People’s Library of Occupy Wall Street

Librarian Is Still My Occupation: Another Epilogue to the People’s Library

Beyond the Prototype: Libraries as Convivial Tools in Action

Modeling a Different World: Libraries and Prefigurative Activism

Where Are They Now? Whatever Happened to the People’s Library