Authoritarian and Democratic Technics, revisited

“The viability of technology, like democracy, depends in the end on the practice of justice and on the enforcement of limits to power.”

– Ursula Franklin

I.

Is technology a problem for democracy, or is democracy a problem for technology?

When times are good that is the type of question that academics and activists wrestle with, but which much of society is happy to ignore. After all, merely to suggest that this is a question cuts against the common sentiment that technology (which in its popular usage is really just a shorthand for computers and Internet associated things—not all technology) and democracy are copacetic. But then there are moments when tech companies take aggressive steps (like banning President Trump from their platforms), demonstrate their power over other platforms (Amazon giving Parler the boot from Amazon’s cloud services), and desperately try to claim that an insurrection against democracy was not organized (and encouraged) using their platforms, services, and devices. In such moments it becomes clear that questions about democracy and technology cannot be limited to academic and activist discourse—though it is a shame that it often takes profound societal crises for such discussions to begin occurring.

While academics and activists have been challenging the idea that technology is “neutral” for quite some time, it is an idea that is still held by much of the larger society. Though those who study technology have emphasized, for years, that technological systems and technological artifacts carry the values and biases of those who create them, there is still a widespread temptation to say that what ultimately matters most is how something is used. Such moves work to shift the onus of responsibility off of the technologies (including those who built them and those who run the tech companies) and onto the individual users. This stance is certainly one that many tech companies have been happy to take, insofar as it gives them something of a pass for allowing everything except the most clearly illegal content on their platforms and devices. Yet the stance gets shaken when such platforms suddenly feel compelled to take significant action out of a fear that they may have some legal exposure. And in such moments the mix of rage (for not doing something sooner by some, for doing something at all by others) gets directed not at the technology itself, but to a handful of figures. The insistence that Mark Zuckerberg and Jack Dorsey take responsibility shifts attention off the level to which the technology is itself complicit.

Even among those who know that technology is not neutral, there is often a tendency to place the blame on a selection of easily-vilified tech company CEOs. One comes across this frequently in books and articles that predate the present situation, wherein authors critique the binary attitude of “technology is leading us to utopia vs technology is leading us to a dystopia” in order to argue for a more nuanced middle road…yet within pages of denouncing that binary many of the same authors come around to admitting that they actually consider themselves to be quite optimistic about technology. It is almost a cliché in works that are critical about technology that the author must preface their critiques by stating how much they love technology. And thus over and over the emphasis falls on dreaming up ways in which Google and Facebook and smartphones and the Internet of Things can be reformed, without considering that in some cases it may be that some of these things cannot be reformed but must be dismantled. To be clear, it would be crass technological determinism to suggest that our present societal problems are solely the fault of our romance with technology, but to act like technology (still a problematic shorthand here) has not played a role in getting us to this moment is equally foolish.

In the wake of January 6, 2021, there has been (and there will be much more) consternation about social media, tech companies, location tracking, and facial recognition—but lurking beneath all of these is a larger question that needs to be addressed: is technology a problem for democracy, or is democracy a problem for technology?

II.

In a short article, that appeared in the Winter 1964 issue of the Society for the History of Technology’s journal Technology and Culture, Lewis Mumford argued that there have been two dominant trends technologies throughout history: “Authoritarian and Democratic Technics.” The older of the two, “democratic technics” tended to be relatively simple, locally controlled, relying primarily on human (or animal) power, and these adapted themselves to the conditions in which they were deployed. By contrast, “authoritarian technics” were complex, situated control in the hands of distant technicians/bureaucrats/rulers, relied on harnessing large amounts of power, and instead of being adaptable to already existing conditions altered those conditions to make those conditions adaptable to the machines. While “democratic technics” could be traced back to the earliest examples of human tool use, Mumford pinned the emergence of “authoritarian technics” to the development of kingship and the organization of “complex human machines” which were deployed for creating many of the feats of the ancient world. For centuries the two types existed side by side, particularly as agricultural work continued to occupy a large part of the population, but over time new complex technologies began to emerge that centralized more and more power in the technological system (and those who controlled it). If the “pyramid builders” were the stewards of the “authoritarian technics” of old, Mumford argued that “the inventors of nuclear bombs, space rockets, and computers are the pyramid builders of our own age” – entranced by the power of their creations. Though “authoritarian technics” require the services of a devoted priesthood (made of the technical, scientific, and managerial elite), Mumford emphasized that it was unwise to focus overly heavily on the priesthood for “the center now lies in the system itself, invisible but omnipresent.” Writing in 1964, Mumford was of the opinion that it was “authoritarian technics” that were in the ascendent position.

Lest there be any doubt, Mumford acknowledged that “authoritarian technics” are frequently responsible for impressive feats that testify to the power of the system (and by extension the power of the humans close to that system), yet Mumford did not locate their success solely in their ability to inspire awe. Rather, Mumford explained the dominance of “authoritarian technics” by understanding how such technics had ironically entered into a sort of “democratic-authoritarian social contract” wherein members of the community were provided with a share of the material abundance created by the system in exchange for their compliance with it. Thus, the cornucopia of mass-produced “goods” (ranging from foodstuffs to entertainment products to consumer electronics) came to act as a powerful stand in for “the good,” in what Mumford characterized as “the bribe” offered by “authoritarian technics.” Those who accepted this “bribe,” were not an army of fools; after all, the “bribe” was only successful insofar as it appeared to be a fair trade to those who were offered it. Yet, Mumford ominously warned that “once one opts for the system no further choice remains.”

There is no denying that Mumford had a tendency to see foreboding signs on the horizon, but his description of these two types of technology was not meant as a funeral dirge, but as an attempt to sound the alarm. For the problem with “authoritarian technics,” as Mumford argued, was not only the threat they represented to “democratic technics” but to the idea of “democracy” more broadly. Writing in the midst of the Cold War, Mumford feared the loss of political autonomy as people found themselves increasingly reliant on (and therefore at the mercy of) complex technological systems over which they had no control (and about which they had little understanding). Having been “bribed” into delegating ever more power to the technological systems (from computers to nuclear bombs), it became increasingly difficult to wrest any of that control back. In explaining the objective of his article, Mumford stated that he was hoping “to persuade those who are concerned with maintaining democratic institutions to see that their constructive efforts must include technology itself.” If allowed, “authoritarian technics” would steadily and happily remake the world in its own image, passing out “bribes” as necessary to secure compliance. “Authoritarian technics” held onto power by convincing the broader society that what was good for the technological system was good for the broader society, and for democracy to survive it would be necessary to shift the focus back to ensuring that technology is made to serve society not the other way around.

III.

Facebook did not develop a conscience on January 6, 2021. Neither, for that matter, did Twitter or Google or Apple or Amazon or [insert the name of whatever other tech company you are currently thinking about]. These companies did not cave to the demands of a “woke mob,” and they did not fail to defend the first amendment rights of their users. These are not democratic platforms or technologies, and contrary to what right-wing media might scream they are not Democratic platforms or technologies either. They are large technological systems that require users to abide by lengthy terms of service, while those users are simultaneously subjected to constant surveillance and manipulation. Most of these platforms have spent years being informed by researchers and civil society groups that their platforms are rife with activities that violate the terms of service to which all users agree, and that their platforms have become hubs for calls for violence. Furthermore, many of the platforms have been fairly open in acknowledging that some activities and some accounts (such as Trump’s twitter account) were allowed to continually flaunt the platform’s rules. People have spent years asking Twitter to “do something about all the Nazis on here,” but Twitter kept replying with shrugs. A review of the testimony these companies’ CEOs delivered when dragged before Congress leaves little doubt as to the loathing these companies have for democratic oversight, and the degree to which their CEOs feel as though they know what’s best. And though it is a popular right-wing talking point to accuse tech companies of having a liberal bias, anyone who has ever watched a video game review on YouTube and then been recommended a conspiratorial right wing broadcaster, has reason to look askance at such accusations.

The tech companies do not have consciences, but what they have is robust legal and PR departments. It is already quite clear that there will be some very steep consequences for the individuals and groups who attacked the Capitol, and as the investigations proceed there will be a fair amount of attention that inevitably comes round to the various platforms that were used for planning and coordination. And when the court documents are made public, it is fairly certain that platforms like Facebook and Twitter and Parler (which until recently used Amazon cloud services) and YouTube will be noted as places where the attackers were radicalized and as places where the attack was coordinated. The tech platforms are constantly monitoring what is said/written/uploaded to their platforms, and a day is coming soon when they will be asked to account for just how long they allowed certain messages to be disseminated. Many tech companies will try to claim that they did not know what was happening on their platforms, or their executives will seek to deflect the blame to other platforms, but the already tarnished image of many of these companies is going to take another hit, and there may be legal consequences as well. When hearings are held on what occurred, tech company CEOs will almost certainly be asked why they didn’t do something sooner, and they at least want to be able to respond that when the moment came they finally did something. Trump was great for business for a time (he certainly made it so that Twitter was an important place to be), but Trump’s time is coming to a close, and the companies that happily profited off of his violent vitriol are now suspecting that it’s a shrewd business move to cut him off.

The tech companies are acting not out of a desire to protect democracy, but out of a desire to protect themselves from democracy.

IV.

Not too many years ago, though it seems like ancient history, it was fairly commonly argued that smartphones and social media were ushering in a golden age of democracy. It may be difficult to remember now, but men like Zuckerberg and Dorsey were touted for a time as great benefactors. Indeed, the smartphone and social media were held up not only as tools that could be used for democratic movements but they were framed as somehow being inherently democratic. The Trump years have been the rock against which such ideas have been smashed. Of course, like a smartphone with a splintered screen, that adoring ideology still works, even if the cracks are showing.

The tech companies seem to neatly fit Mumford’s definition of “authoritarian technics.” They are large complex technological systems that seek to remake life in their own image, they seek to be all knowing, they rely on the fealty of a feted class of skilled high priests, they keep their inner workings secret, they gradually work to ensure that there are no real alternatives to themselves, and they carefully ensure that a share of the goods are distributed so as to suppress rebellion. Certainly, there are particular individuals who are presented as being in charge (such as Zuckerberg and Dorsey), and yet (without wanting to give them a pass in any way) it often seems that these figures have lost control of what they have built. Zuckerberg and Dorsey have a lot of responsibility, a lot of power, and a lot of guilt—and yet to a certain extent they are also cogs. It’s fun to blame Zuckerberg (he deserves plenty of blame), but too often blaming Zuckerberg distracts from the need to blame Facebook more broadly. Or, to put it slightly differently, blaming Zuckerberg and Dorsey helps perpetuate the idea that these companies can be reformed with slightly better management. But these companies are just the public facet of an authoritarian technology, a kinder manager may be more deft at distributing the “bribes,” but ultimately it is the system itself that is objectionable, not just the CEO. If Zuckerberg is forced out, and he has to spend the rest of his life tinkering in one of his many garages in one of his palatial estates, the problems will continue. And this is not only true of Facebook.

It is not an exaggeration to say that large tech companies, and large technical systems, have amassed a great deal of power in contemporary societies. And it is not an exaggeration to say that as online spaces have become new sorts of “public squares,” the ability to give people the boot from those “public squares” has meant that these companies play a large role in determining what can be said and who can say it. Furthermore, though banning a President’s accounts certainly draws attention to the matter, it is foolish to act as though this is the first time that these platforms are stepping in to control and monitor speech. Access to that digital “public square” is one of the “bribes” that these platforms have offered up, where being able to speak in this space is given in exchange for subjecting yourself to subjecting (and to letting your words be monetized). Yet, as these systems have taken more and more power the “bribe” has steadily shifted into a sort of blackmail—wherein these systems keep people engaged no longer by promising them a share in the goods, but by telling them that if they try to leave they’ll no longer be able to participate in society.

If we are truly concerned with preserving democracy, flawed democracy, imperfect democracy, democracy that scarcely deserves to be called democracy, we need to seriously ask ourselves if the technological systems on which that society relies are themselves democratic. Truly wrestling with this problem requires a deeper and more uncomfortable conversation than one that simply singles out those popular villains like Facebook and Google. It is a conversation that requires us to go deeper than just the platforms to ask the thorny question about whether or not the technologies upon which those companies/platforms rely are themselves part of the problem. It seems that many people are increasingly willing to denounce Facebook, but if you want to criticize Facebook at this point you also need to be willing to have a difficult conversation about computers and the Internet.

What would genuinely democratic social media look like? What would genuinely democratic computers look like? What would a genuinely democratic Internet look like? Are such things even possible? Was it always a dangerous fantasy to believe that Cold War technologies of surveillance and control could be turned in truly liberatory tools? It is hubristic to claim to have a definitive answer, but it seems that if we want to really talk about democratic computers a good place to start would be an acknowledgement that these machines are filled with rare earth minerals extracted in violent conditions, that they are assembled in high-tech sweatshops, and that after planned obsolescence swiftly claims these machines they eventually go on to leech toxins into the water far from where the machines were enjoyed. Sadly, there is nothing new about a country proudly calling itself a democracy while relying on systems of violent extraction, human exploitation, and ecological destruction. But if talk about democracy is more than just whitewash this history, and these conditions, cannot simply be ignored.

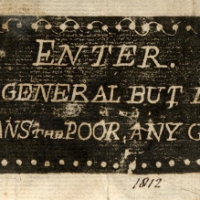

Historians of technology and scholars who study media have long debated about the significance of the printing press for the development of democracy and democratic movements. This is not the space to present this voluminous literature in detail, suffice to say there are some who argue that the role of printing cannot be discounted in democracy’s development while others pushback on a narrative that they fear reeks of technological determinism. And yet, approached from a different angle, the printing press can fit into a different story about democracy and technology. Not one that suggests that a printing press leads to democracy, but one that suggests that a printing press, as an artifact, is an example of a “democratic technic.” After all, equipped with relatively basic blueprints, some not uncommon materials, and a smallish sum of money—it is likely that you and a dozen of your acquaintances could build and begin operating a printing press in your community. Of course, this doesn’t mean that what you decide to print will be “democratic” material, but the technology itself will be of such a scale that it can be understood/used/regulated by the community. But it would be much more difficult, even with excellent blueprints, for you and a dozen of your acquaintances to make a smartphone (where will you get the rare earth minerals?) or the Internet.

To be absolutely clear, this is not to romanticize a past of printing presses and water wheels, nor is it to pine nostalgically for the halcyon days before smartphones. Those days weren’t so great either. Besides, we have to walk forward, not back. Yet that doesn’t mean that we have to keep walking in the exact same direction that we have been going just because we’re already so far down this path.

In the coming weeks and months we will see all manner of proposals for reigning in the tech companies. Some of these will call for greater regulation, some of these will call for treating them as public utilities, some of these will call for being even more hands off, and some of these will call for certain CEOs to step down in disgrace. Many of these ideas and proposals will have real merits, but an “authoritarian” technology operated with a bit more “democratic” oversight is still an “authoritarian” technology. The challenge in this moment is not to be satisfied by calls for a bit more “democratic” oversight, but to confront the fact that certain technologies have no place in a democratic society. In a democratic society, it is not any single person’s place (not yours not mine not Zuckerberg not Trump) to say which technologies to allow and which to disallow—that is a question that has to be answered democratically.

V.

So, is technology a problem for democracy, or is democracy a problem for technology?

We are currently living with the consequences of what happens when technology is given free rein to remake society in its own image, its long past time to see what technology looks like when it is remade in democracy’s image.

Related Content

The good life or the goods life – on the thought of Lewis Mumford

Beware Silicon Valley’s guilty conscience – on the Center for Humane Technology

What technology do we need? – on the Personal Democracy Forum

Living well in the technosocial world – a review of Technology and the Virtues

Technology and the society we want to build – a review of The Whale and the Reactor

Pingback: Omnium Gatherum: 17jan2021 - The Hermetic Library Blog

Pingback: Progress for the status quo – on the Chamber of Progress | LibrarianShipwreck

Pingback: They meant well (or, why it matters who gets to be seen as a “tech critic”) | LibrarianShipwreck

Pingback: Theses on Technological Pessimism | LibrarianShipwreck

Pingback: Imagine the End of Facebook | LibrarianShipwreck

Pingback: The Authoritarian Mindset: How to Learn to Stop Worrying and Love the Cop in Your Head – Ravenwood

Pingback: Theses on the Techlash | LibrarianShipwreck

Pingback: “Computers enable fantasies” – On the continued relevance of Weizenbaum’s warnings | LibrarianShipwreck