A RoboCop Statue Amidst the Rubble – Distraction, Dystopia, Detroit

In dystopian fiction, the path that led to these crumbling civilizations is obscured by a haze of ash. While there may be general allusions to the historical event (a calamity of some sort or another) that birthed this new order, most dystopias are not the tales of the slow birth of oppressive technocratic and bureaucratic regimes but the confrontation of the reader or viewer with these fully grown structures.

From 1984 to Brave New World to Brazil to Gattaca to V for Vendetta to The Hunger Games these tales are not of the ascendance of the power structure, but the tales of those (often unsuccessfully) struggling against a power structure the start of which they were not around to stop. Certainly some of these stories contain suggestions that the protagonist is descended from those who had resisted (perhaps Winston’s “disappeared” parents in 1984 or Evey’s “vanished” parents in V for Vendetta); such links to a resistant past allow for the rise of the new oppressive power to be referred to in half remembered flashbacks, or chunks of exposition. The dystopia has come and the tale of how it arose matters little, as clearly the attempts to thwart it failed.

Thus, dystopias are odd warnings for those who look warily upon socio-political events. It is easy to invoke 1984 or Brave New World or Fahrenheit 451 in reference to some current occurrence, yet these can frequently come off as almost laughably hyperbolic. After all, things may be bad, but to compare them to the authoritarian state ruling over the rubble in a dystopia seems a stretch. Such links would be easier to draw if one could more easily point to the warning signs that lead to such states, but the minor steps are usually given little attention in dystopian tales whilst the “catastrophic event” that causes the final push, is what usually gets highlighted. Few dystopian tales are catalogs of the thousands of minor occurrences that allow for the dystopian turn, yet for such a regime to seize power post “catastrophic event” there must have been thousands of small scale oppressions that built up the skeleton upon which the dystopian skin could be sewn.

Dystopian tales play upon fears of a much more immediate and disquieting notion than horror movies. The allegory is hidden deeply enough in zombie entertainment and other standard scary fare to not overly invade our personal quiet. After all, we know (or are at least fairly certain) that we won’t ever have to deal with zombies, but an all powerful surveillance state backed up by a militarized police force? That seems much more possible. Thus dystopian fiction provides a release for the anxieties that we are not fully able to name. As the staying power of dystopian story telling demonstrates, it latches onto a real anxiety amongst people, albeit an anxiety that can easily be turned away from systemic critique and into mass culture entertainment. It is as Theodor Adorno described in The Schema of Mass Culture (collected in The Culture Industry):

“Mass culture is a kind of training for life when things have gone wrong.” (Adorno, 91)

The power of dystopian imagery in our cultural imagination has made some of these works the go-to allegories for a world in which things seem to be slowly sliding towards the dark events foretold by dystopian writers. Indeed the term “Orwellian” has been thrown around often as the NSA revelations continue, and sales of 1984 have jumped impressively (though this “jump” may be less impressive than it may sound). We may not be living in Oceania, but we know that somebody is watching. What remains missing is the foretold catastrophic event.

Yet this danger, and the strength of dystopian thinking, is on odd display in many seemingly “respectable” areas, it is not just the province of the paranoid. Writing in the aftermath of the early NSA revelations New York Times columnist Thomas Friedman penned a warning in support of the actions of the NSA (“Blowing a Whistle”). Friedman’s argument hinged upon the notion that while the spying was bad, what would be worse was another 9/11. Or, to put it in a properly dystopian tone, an event worse than 9/11 such as a nuclear event that would lead people to demand that the government take up even more spying powers in the name of “safety.” Friedman’s article invoked the cultural “training” of dystopias to justify seemingly dystopian tactics (mass surveillance) in order to say such tactics provide protection from a true dystopia.

Thus Friedman reveals himself to be another reader of the end results of dystopias, without thinking how those end results are reached. Reading an authoritarian state as an exercise in modus ponens logic is what is at work for Friedman: if there is another major terrorist attack, than the government will take on ever more surveillance and policing power. Catastrophes can lead people to temporarily suspend their critical thinking, as the passage of the Patriot Act proves, but what has been revealed about the NSA is a rather different matter. Namely, that these massive spying and policing apparatuses already exist and are already at work. They did not need some new “catastrophe” to start, and did not need some new “catastrophe” to be put into action.

What recent events show is that the “open society” that Friedman praises, is much less “open” than he would have his readers believe, it is simply a mask: a thin glimmering image of a smiling nation behind which is a sophisticated listening and tracking device (this could easily be called a smart phone or a social network). It is not a matter of declaring that our world has become a dystopia – such would be gross hyperbole – but to recognize where the groundwork for such an unwanted state may be being laid. By alluding to the deep paranoia that culture has built up toward dystopias, by using the dystopias as abstractions instead of dangerous possibilities, these highly suspect tactics deployed in the real world can be portrayed as protection from a dystopian state. Thus mass surveillance ceases to be seen as Orwellian but is described as a safeguard against an Orwellian state.

While dystopias emerge as popular and well-known products in the culture industry (ones that have lost much of their subversive edge) the invocation of the doom and desolation is used to warn against actively challenging the status quo; after all, things may be bad but it isn’t “dystopia bad.” This clever trickery executed by the culture industry was described by Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer in Dialectic of Enlightenment thusly:

“What is decisive today is no longer Puritanism…but the necessity, inherent in the system, of never releasing its grip on the consumer, of not for a moment allowing him or her to suspect that resistance is possible. This principle requires that while all need should be presented to individuals as capable of fulfillment by the culture industry, they should be so set up in advance as eternal consumers, as the culture industry’s object. Not only does it persuade them that its fraud is satisfaction; it also give them to understand that they must make do with what is offered, whatever it may be…Entertainment fosters the resignation which seeks to forget itself in entertainment.” (Adorno and Horkheimer, 113)

Justified paranoia is integrated and expressed through the culture industry and the citizen’s desire for resistance is provided the stand in of the (usually doomed) tragic dystopian hero. The dystopia on screen acts as a protective blanket viewers wrap themselves in to shield themselves from actual dystopian trends. Anxiety at the “fraud” of the dystopia on screen provides a resistant “satisfaction” that inures us to the steady erosion of our own liberties.

Perhaps the clearest recent example of this dance with dystopian imagery comes less from the NSA revelations and more from Detroit’s recent declaration of bankruptcy. It is worth keeping in mind that the filing for bankruptcy was executed by the city’s “Emergency Manager,” a person whose authority overrides the city’s elected officials though the Emergency Manager had not been elected to the role (as one might expect in a Democracy [this bankruptcy is being challenged in court]). The announcement of Chapter 9, was followed by no shortage of people (particularly on social media [itself a manifestation of the culture industry]) making references to the character RoboCop. As a fairly iconic late 1980s film, RoboCop is a rather dystopian tale (the setting more than the cyborg) in which the Detroit of the future has fallen into such economic dire straits that a huge corporation has pretty much taken over the city – including the police force – and are advancing plans to systematically divest the current citizens in order to build a gleaming city of the future. The long-term plans may be for a world out of Huxley, but the tactics are to be straight out of Orwell.

Detroit’s current fall into financial woe is for the citizens of the city a collapse; and a reminder that the disaster need not be the optically stunning nuclear blast but can be the ongoing hammering done by our economic system. It may be too early to tell exactly what will happen in Detroit, though there are at least some groups with Ayn Rand worthy libertarian fantasies that seem borrowed from the corporation in RoboCop. Yet the invocations of that film franchise act in a funny way, they reference a character in a horrific setting yet they simultaneously pose a desire for some farcical savior as the remaining hope (RoboCop not the people [and don’t bring up RoboCop 3]), and once more the seeds of genuinely threatening and worrisome real world conditions are buried under the rubble of mass culture. Crowd funded plans for a RoboCop statue in Detroit may be going ahead, but it seems that this shall simply be a statue watching over rubble, a testament to people partaking in dystopian paranoia and ignoring the warning signs. A RoboCop statue is a collective middle finger to ourselves, a statement that audiences loved the film’s gore but are happy to ignore the setting in which it took place…one that looks ever more like actual Detroit. Thus we learn to love the dark ambiance of a dystopian tale and pay no heed to the state of affairs it warns against.

One of the things that should be abundantly clear today is that the threat of the cataclysmic catalyst need not be an actual horrific event – it suffices to simply build up fear of such an occurrence (as Friedman does in his referring to the possibility of another terrorist attack), oppressive systems can be enshrined into law and advanced without there needing to be a massive public outcry of “protect us!” all they require is a docile public. The ongoing insecurity of everyday life has become the catastrophe. Lewis Mumford warned against the dangerous road that such fears leads us down (in In the Name of Sanity) and while he was concerned primarily with nuclear war, his words remain apt:

“our own leaders are now living in a one-dimensional world of the immediate present, unable to remember the lessons of the past or to anticipate the probabilities of the future: to guarantee national security they have created a state of total insecurity, and in the effort to insure national survival they have perfected weapons whose full-scale use would imperil the future of the human race.” (Mumford, 4)

Certainly, weapons of mass destruction continue to pose a threat to the long-term survival of humanity, but the spying apparatus and the economic apparatus are also weapons that are trained by those in power against their own citizenry. Mass surveillance acts as a powerful disincentive to those who would think of resistance (against these very systems) and economic instability places people in such precarious states that they fear taking any steps that would jeopardize the scraps they are still allowed to cling to. The dangerous weapons are the instruments for turning an “open society” into a dangerously closed one with rapid ease (a technologically embedded bias of which even some of Google’s overlords are aware). And these are tools that are left on the table for use by unscrupulous leaders. If a system has the potential to be grossly misused and abused than the solution is not “better oversight” (which can always be dismissed) but not to put in place systems that can be grossly misused and abused in the first place, and to dismantle the ones that have been built before they can be used again.

At their subversive best dystopian tales can provide powerful warnings against terrible futures, but mass culture has shown itself continually capable of turning acts of subversion into “non-conformist” outposts that only serve to reintegrate resistance into the system. The challenge for those who stand, as we do, at the precipice of an unknown if unoptimistic future is to question and tear down the systems that have the potential to make the future into a nightmare. Paranoia is not in and of itself sufficient resistance, individual acts of non-compliance (though worthwhile) are not enough, and our gleaming consumer gizmos (which are the windows through which we are spied on) are part of the con of which we are the victims.

Unless we can see in dystopian warnings not a demand to accept that things “aren’t that bad” but a warning that things can indeed become that bad, thanks to the systems that have slowly been put in place, we will be unable to thwart a scary turn that may be just a catastrophe away. And those who would praise authoritarian systems as protections against future authoritarianism have forfeited the moral integrity and intellectual clarity to be considered honest in these debates; after all, every dystopia prides itself on its propagandists, the incipient ones too.

Remember, Big Brother laces on his jackboots slowly, while the final tying and jumping to attention may seem the sudden result of a catastrophe the fact is that the boots had been laced in preparation for that moment.

The choice is ultimately ours whether a statue of RoboCop will be an ironic emblem of fears we have defeated or if it will be a cold testament to a warning we ignored whilst the decaying statue gazes out across the blighted rubble.

Works Cited:

Adorno, Theodor. The Culture Industry. Routledge Classics, 2001.

Horkheimer, Max and Adorno, Theodor. Dialectic of Enlightenment. Stanford University Press, 2002.

Mumford, Lewis. In the Name of Sanity. Harcourt, 1954.

Some dystopian fiction does a better job of approximating our reality, where things just kind of slide into decaying, disfunctioning horror. Margaret Atwood, Sarah Hall & Octavia Butler come to mind; for some reason female authors seem to have grasped the concept rather well.

Pingback: Falling Under Technology’s Spell – Chromecast | LibrarianShipwreck

Pingback: How Not to Heed a Warning | LibrarianShipwreck

Pingback: If the NSA is the Fever, is the Internet the Disease? | LibrarianShipwreck

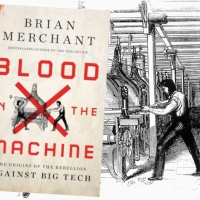

Pingback: Luddism for These Ludicrous Times | LibrarianShipwreck

Pingback: Ludismo para estos tiempos Ludiculos | blognooficial

Pingback: Asistir a una manifestación de protesta (por cualquier causa) con un teléfono inteligente en el bolsillo es traer a un policía y a un espía corporativo con ustedes. | blognooficial

Pingback: The Faucet Goes Dry in Detroit | LibrarianShipwreck