The Specter of General Ludd at SXSW

The SXSW festival, held annually in Austin, Texas, is something of a bacchanal to the new. While many are familiar with the festival for its music and film components it is, perhaps, the “Interactive” section of the fest that commands the greatest cultural effect. For example: many of the bands who played at SXSW in 2007 have sunken back into obscurity (or broken up), but the true star that exploded out of SXSW that year was Twitter.

My point? SXSW is not the place that one goes to hear technology, and the various applications such gadgets run, denigrated. Certainly, there are always an assortment of media theorists and skeptical scholars present to provide a breath of reason amidst the fawning, yet such voices always seem somewhat like they have been invited precisely so that they can be disregarded. Which is why New York Times writer Jenna Wortham’s recent reminiscence of SXSW (posted March 22, 2013) is particularly interesting, it is titled: “The Best Thing I Learned At SXSW Was From the Unabomber.”

It is a sensational headline, and though unkempt beards may be seen wandering around SXSW none of them are that of Ted Kaczynski (he who is better known as the Unabomber). The truth of the matter is that Wortham probably should have swapped out the word “Unabomber” with the words “a Professor who is highly critical of technology,” but then fewer people would have read her article.

The professor in question is David Skrbina (of the University of Michigan-Dearborn), who could safely be called a technological skeptic (though it is easy to imagine him being disparaged with such epithets as “luddite” [by those who know little of the history of Luddism] or “technophobe”). Skrbina is Wortham’s link to Kaczynski, as Skrbina has corresponded with Kaczynski and has helped publish a collection of Kaczynski’s writings.

Wortham and Skrbina do not discuss Kaczynski’s crimes (and I won’t either), but instead discuss his critique of technological civilization, and the negative elements that sneak in amidst the celebrated bits. Skrbina is presented by Wortham as something of an odd character at SXSW, and it is not an entirely unfair characterization as Skrbina is not to be found on Facebook, and is described as carrying with him an aged flip phone. Amidst a mass of uber-digitally-connected folk, Skrbina certainly is the odd man out.

Skrbina was at SXSW to participate in a debate titled: “What Can We Learn from the Unabomber?” in which he was clearly the side arguing that something could be learned (though not tactically [the even featured a hashtag of “unabomber” making me wonder if the whole thing wasn’t a Dadaist prank of some sort]). The slides from the debate have been posted on-line, and flipping through them (they are posted for Skrbina as well as the other debate participants) one can get a very basic outline of the premises of the debate. The technological stance that Skrbina seems to be reccomending looks as if it mainly calls for people to be more skeptical regarding their gadgets, he poses the sort of non-binary questions that technology and technophiles frequently struggle with (the questions rather reminded me of Neil Postman’s 6 Questions for Technology).

Yet Skrbina’s points seem to me less interesting (in this context) than the article in which he is being mentioned. Not to be rude but if you are a professor who does not own a cell phone (nothing wrong with that) who has helped publish a collection of the Unabomber’s writings…well…it isn’t hard to guess your technological views. It’s also relatively easy for those disagreeing to dismiss these ideas as belonging to somebody living in the ivory tower instead of reality (even as the ones voicing this critique could be accused of spending more time in a digitally constructed world than actual reality). And thus, in this context, the opinion of a tech reporter for the New York Times such as Wortham comes across as much more interesting. As Wortham writes:

“My eyes were glazed over, after hours of looking at apps and hearing people talking about how their new social thing was going to be the Next Big Thing. It didn’t feel neutral and it didn’t feel optional. It felt inescapable.”

and

“At SXSW, the culture of pervasive technology becomes so overwhelming you don’t even notice it. It seeps into everything.”

Wortham notes that Skrbina’s views and Kaczynski’s are extreme (though it is rather unfair to call them “extreme” in the same sentence), and she is unconvinced by their suggested solution of simply swearing off technology. Such, Wortham claims, is unrealistic. And, let’s be honest, it largely is. Yet, what matters is that the lesson that I think that Skrbina was truly trying to impart had an impact on Wortham: it encouraged her to think critically about technology, and perhaps to realize that such critical thinking is seldom given proper shrift (as Wortham realizes at the end of her piece when recalling the reaction against her voicing skepticism towards Google Glass).

Alas, I think that the tragedy of the piece can be found right in the title. For any discussion of these real issues and questions regarding technology can be too easily bogged down into the sensationalism around “The Unabomber” (which may have been part of the point). When technological skepticism is put forth as the provenance of solitary professors and maximum-security-prisoners it deflates some of the force of these questions. After all, there aren’t many people eager to get into a debate where they’re forced to defend the Unabomber (they may go in trying to defend his ideas about technology and get forced into explaining [at length] that they do not condone violence).

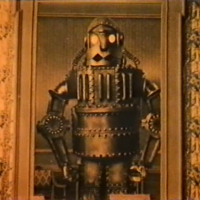

While such skeptical voices are often called “Luddites” such is the perfect time to reclaim—and proudly—this term for what it means. It is a shame that Skrbina highlighted the actions of Kaczynski when he could have used the opportunity to provide his listeners with a brief history of the actual Luddites. As historian David F. Noble describes them:

“The Luddites who resisted the introduction of new technologies were not against technology per se but rather against the social changes that the new technology reflected and reinforced.” (7)

Or, as the writer Kirkpatrick Sale describes:

“The real challenge of the Luddites was not so much the physical one, against the machines and manufacturers, but a moral one, calling into question on grounds of justice and fairness the underlying assumptions of this political economy and the legitimacy of the principles of unrestrained profit and competition and innovation at its heart.” (5)

The Luddites were a mass movement of people, not just one skeptical voice speaking at a conference. Though most know of the Luddites for the form that their protest eventually took (smashing the looms), it is important to know that this was not an unthinking technophobic reaction. Indeed the Luddites were workers who saw the future of misery that the machines would bring and they fought against it. The Luddite protest against the “social changes that the new technology reflected and reinforced” is a protest and challenge that has been sorely lacking of late.

Hopefully voices such as Skrbina can help influence a rebirth of a true Luddite spirit (a mass movement standing in opposition to “machinery hurtful to commonality” [as the Luddites themselves described it]), instead of inspiring people to act out a lonely fantasy of an unwinnable war against the mechanical leviathan.

Though Skrbina’s critique may have influenced Wortham (or at least given her cause for contemplation) the fact remains that when such thoughts are invoked side by side with a name like Kaczynski these views then take on the sound of the howls of crazy lone wolves barking incessantly at the glow of a computer screen that they’ve mistaken for the moon.

The emphasis should not be on the howling, it should be on questioning how we have substituted the computer screen (and smaller screens) for the moon.

This post references two books:

Noble, David. Progress Without People. Between the Lines (1995).

Sale, Kirkpatrick. Rebels Against the Future. Perseus Publishing (1996)

Once again this has proven to be one of the most insightful and well-written blogs I’ve come across on WordPress. Don’t stop writing. Also, I know it’s cheesy and a bit beneath the academic/intellectual level of your blog, but I’d like to nominate you for a Liebster Award. If you choose to participate, you can check out the details here: http://wheelofwhy.com/2013/03/27/liebster-award/ Keep up the quality work.

Pingback: One Weekend in the Woods is not an Ideology | LibrarianShipwreck

Pingback: Trading Sledgehammers for Pillows: the curious case of Reform Luddism | LibrarianShipwreck

Pingback: Fighting Fire with Arsonists | LibrarianShipwreck

Pingback: Who’s Afraid of General Ludd? | LibrarianShipwreck

Pingback: ¿Quién tiene miedo del general Ludd? | blognooficial

Pingback: The Luddite Response | LibrarianShipwreck

Pingback: Who Was Captain Swing? | LibrarianShipwreck